One of the shortcomings of figurative art, across time, is that it fails to convey the true meaning of a moment because of its sheer literalism. This failure is most easily understood in photography, where the photograph supposedly captures a slice of life. The moment captured by the photographer, however, is not at all like the actual experience of the person captured in the photograph.

For starters, we cannot see ourselves with exactitude as the very act of capturing the moment distorts our memory with the photographer’s vantage point. Also, everything is frozen in time. The exactness of the image, then, gives a false sense that all meaning is captured, when in reality, it is just beginning. This dilemma, as represented in the human experience of trauma, is beautifully addressed in Cy Gavin’s solo show Overture, which opened to a packed, exuberant crowd on July 15th at Sargent’s Daughters.

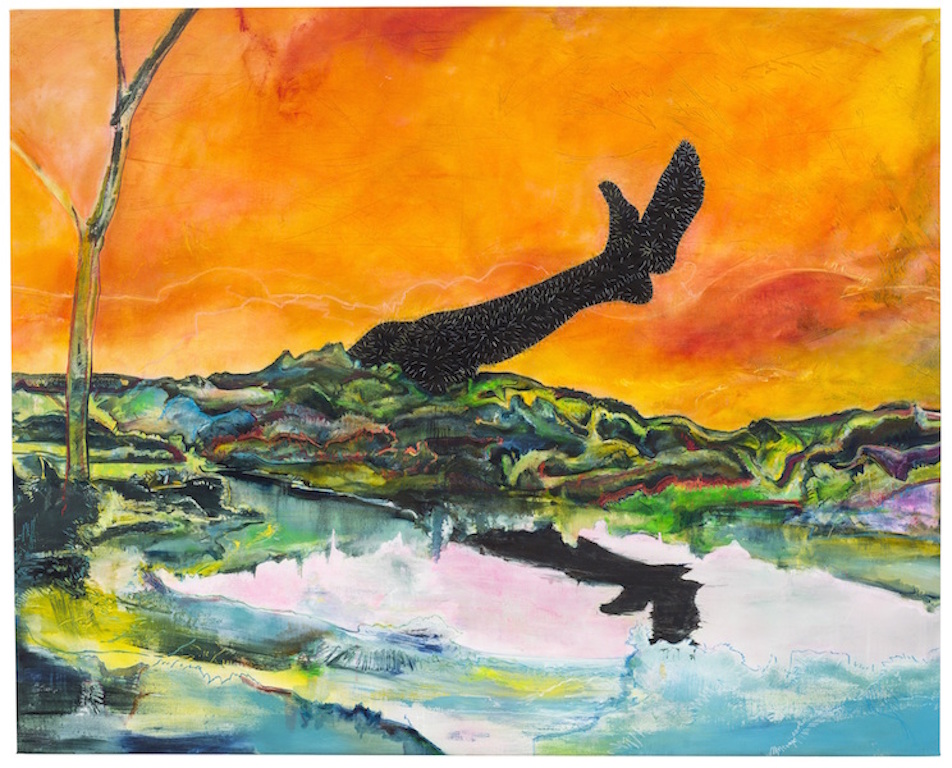

Gavin’s paintings overtly or inadvertently the redemptive reconciliation that follows trauma. The exclusive subject of his paintings is black figures, usually men, in horrifying predicaments. The show’s signature work, Spittal Pond, Bermuda, depicts two black legs, the last glimpses of a man buried alive perhaps, coming out of a stunning, surreal landscape. Another untitled image is of a dark figure in a beautiful polar landscape, his black, curly hair having grown into an enormous boulder that pins him prone against the frozen land.

The images capture the experience of racial, sexual, or other human suffering. The significance of the moment is not fully realized at the moment it happens. Rather, it occurs weeks, months or even years afterwards, usually upon reflection or through dreams. Haunted by the event, the subject comes closer to a realization of its meaning and what it continues to mean in relation to one’s new experiences over time. Thus, the landscape of the change is not just as it was. It becomes surreal–part of the present and the past, the literal and the imaginary– a fluctuating setting that blends the impressionistic with the fantastic.

What makes these paintings about trauma so beautiful? The beauty lies in the bravery that comes with the determination to “never forget”. Furthermore, only by reflecting on the moment in which our lives were inexorably changed, can we actually come to terms with what happened and move forward. The self is ripped in two, but upon reflection, the part left at the site of the crime is merely the shadow self. Indeed, despite the disturbing elements, the images evoke peacefulness. We realize that what we see is only the shadow.

According to Thoreau, “every man casts a shadow; not his body only, but his imperfectly mingled spirit”. Gavin’s deep black figures, painted using a combination of tattoo ink, acrylic and oil, are Thoreau’s shadows, reconciling fate.

RSS

RSS