Courtesy Michael Werner Gallery (New York and Berlin)

An exhibition of twenty-eight truly incredible, even mind-boggling, drawings by an obscure outsider artist was hardly what I expected to find in the parquet-floored galleries of the Upper East Side. First of all, I must preface that I abhor the term “outsider art,” but Schroder-Sönnenstern certainly was never in the ‘front line’ of his contemporaries, and after a little research, I came to learn that he was socially obscure and ostracized. This is visible in his drawings on view (all pencil and colored pencil on cardboard), which are strange and fantastical. As Jean Dubuffet would describe Art Brut (or Outsider Art), these drawings were created from “unselfconscious imagery born of pure, uninhibited expression.”

Schroder-Sönnenstern’s imagery is so unique and bizarre that, as the press release illustrates perfectly, they seem to have been born forth from his mind without iconographic precedent. If these drawings had been made today, it may not have been such a shocker, but imagining an adult making these in the 1950s is a marvelous thought indeed. Schroder-Sönnenstern (b. 1892, Lithuania) was misdiagnosed as schizophrenic at a young age, briefly institutionalized and later arrested. In his late 20s, he created a new identity for himself as Professor Dr. Eliot Gnass von Sonnenstern, a holistic healer and fortuneteller who, rather than keeping any profits, supposedly donated to the poor. He spent much time in jail for various violations, yet it wasn’t until 1949 that he began to draw. (I would suggest reading the press release or the catalog to learn about his life in further detail).

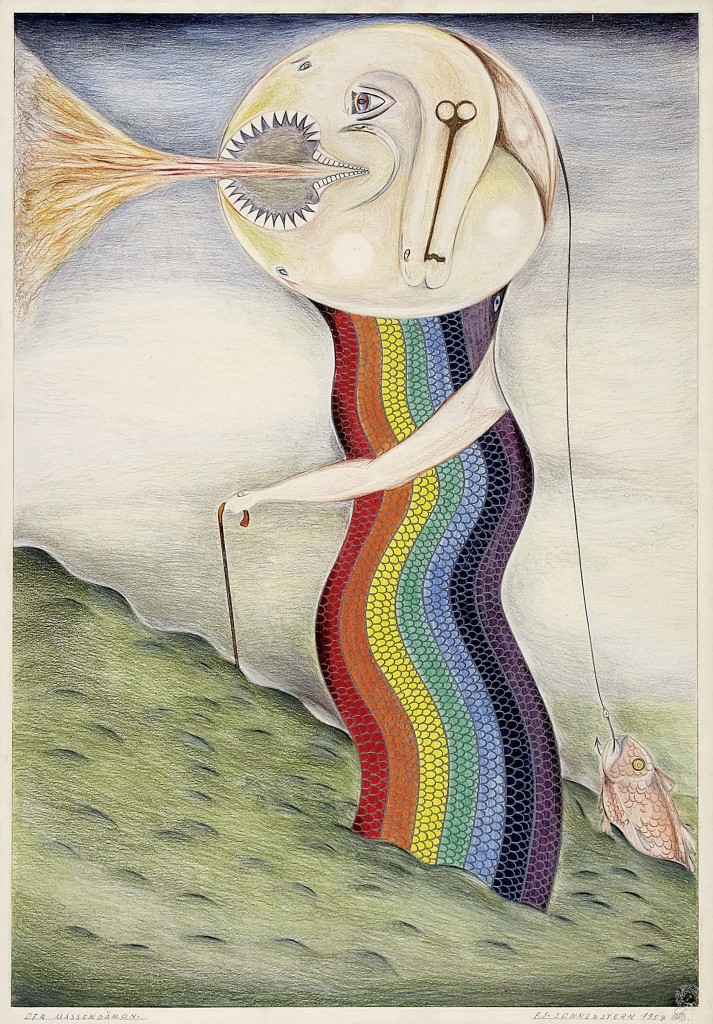

A poly-ocular creature rendered from multiple viewpoints breathes a stream of fire towards the edge of the paper in The Mass Demon (1954). Its brightly colored rainbow scales signify that it is a sort of fish rising from water, yet with one human arm it holds a cane, suggesting that it may also reside on solid ground. Nothing is either here nor there in these scenarios. A toothy serpent either devours or makes loves to an exaggeratedly cleft-chinned, duck-footed (literally) woman in The Jealousy Tragedy, (1956). In Vitanovaseturine, (1951/52) a rotund, winged woman defecates into a glass jar already occupied by a cartoonish heart symbol. Upon the objects and in the margins are scrawled words that may be a narrative, commentary, or perhaps prophecies. What did Schroder-Sönnenstern (or Dr. Gnass) mean to communicate with these drawings? Were they images of personal fantasies, or perhaps pedagogical illustrations meant to convey a particular message?

Works that are heavy with text such as Monument of the Dead (1951/52) bring to mind other ‘prophets’ who conveyed their messages through drawing such as Royal Robertson. Although Robertson made his maniacal, biblically prophesiable drawings in Louisiana mainly in the 60s and 70s, there are formal and thematic similarities between their works.

In The Moon-Moralistic Veneration of the Artist’s Bones, (1957) the artist looks introspectively at his life after death. On his right side, a dog-fish on wheels offers him poison, and on his left, a woman offers food while a dog, or feline creature, offers money. A primate serves him as his feet, while a serpent with an inner-eye resides below. I do not believe that a conclusion really be drawn from any of these clusters of symbols, and rather that one can appreciate these incredible scenarios as just something that is beyond one’s individual comprehension.

Friedrich Schroder-Sönnenstern: From Barefoot Prophet to Avant-Garde Artist

Michael Werner Gallery

March 16 – April 30, 2011

RSS

RSS