An entertaining, animated oral narrator in person, Bryan Zanisnik is also highly talented at telling stories through visually complex works, stacked with symbols, metaphors, and signifiers. In a sort of choose-your-own-adventure visual narrative, the viewer is allowed to piece together the information to create, or re-create, his or her own personal story. Zanisnik photographs complex tableaus constructed from personal and found objects, stages absurdist performances, and shoots videos that follow a New Jersey couple (his parents) through domestic and familiar spaces. His new body of work, Brass Arms Upper Eyelid, is currently on view through February 19, 2011 at Horton Gallery. In conjunction with the exhibition, Zanisnik will present a live performance on Saturday, February 5, from 4-6pm.

Bryan Zanisnik (b. 1979, Union, NJ) lives and works in New York, NY. He received an MFA from Hunter College, attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and is currently an artist-in-residence at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Workspace Program. He recently performed at Galeria On, Poznan, Poland; PS1/MOMA, New York, NY; and Marginal Utility, Philadelphia, PA. This summer he will perform and participate in an exhibition at the Times Museum in Guangzhou, China.

Amanda Schmitt: In comparison to your last show at Horton Gallery, Dry Bones Can Harm No Man (2009), your new photographs are printed much larger. Did this happen naturally, or was the larger space a factor?

Bryan Zanisnik: The increase in the size of the photographs is simply a natural progression in my work. In my last show at Horton Gallery, I was working with film and a medium format camera. In the current show, I am working with a 25-megapixel digital camera attached to a panoramic head. The panoramic head allows me to create high-resolution composite photographs that consist of numerous individual shots that are then stitched together in post-production. While I use Photoshop and a program called PTGui to assemble the images, none of the actual content is digitally manipulated. For example, 18 Years of American Dreams consists of 80 individual shots stitched together. Using a 100mm lens atop the panoramic head, the telephoto lens naturally compresses the space, creating a photograph that appears dense, chaotic and hyper-real.

Are you influenced by movies, books, and other popular culture references? Are any of your works odes or monuments to specific authors, musicians, or celebrities?

The content of my work is influenced by numerous literary and popular culture sources. In recent works, I have referenced everything from James Joyce and Jonathan Safran Foer to Pink Floyd and Neil Young. However, personal memories and histories are more often the starting point for one of my works.*

If masculinity and paternity were themes that ran through Dry Bones Can Harm No Man, could one say that sports and American athleticism are central themes to your current show?

Looking at the subject matter in the new photographs, there are numerous references to sports and sports memorabilia. All of the sports objects used in the photographs are connected to my childhood, and were culled from my parent’s garage in New Jersey. For example, in the triptych Off Season, there are cardboard cutouts and posters of my childhood hero Larry Bird. I remember as a child watching a video clip of Larry Bird mowing his own lawn during the basketball off-season. Looking back on that memory now, there is something extremely idiosyncratic and poetic about a basketball icon mowing his own lawn. Beyond this quirkiness, the memory also feels particularly American.

Can you speak more about your work in relationship to American culture, folklore, and history?

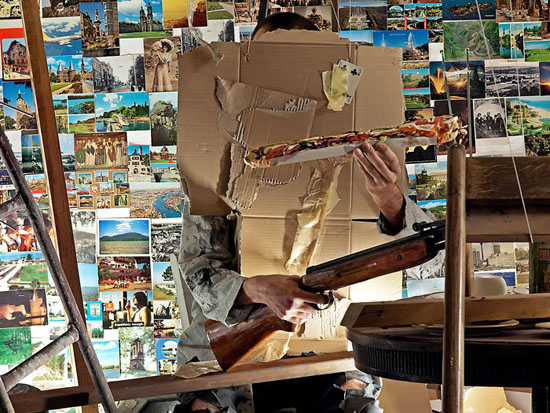

I think of my work as the merging of Americana culture with my own personal culture and history. I am very interested in responding site specifically to locales within the United States, and more recently, I have begun to respond site specifically to spaces abroad. This past summer I built an installation at Galeria On in Poznan, Poland as part of the Mediations Biennale. The installation consisted of numerous communist artifacts from the 1970s and 1980s, including postcards, furniture and tchotchkes, to name a few. At the opening I sat completely still inside the installation for two hours, holding a rifle in one hand and a large polish sandwich in the other hand. The rifle referenced American gun culture, but also referred to the gallery’s location, which was inside the former hunting residency of German Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II.

One Touch Is Never Enough alludes to obsessive-compulsive tendencies, collecting, and even hoarding. How does this piece fit with the rest of the show?

Since soap dispensers are associated with bacteria and health, there is a natural obsessive compulsive and anxiety-ridden subtext to these objects. At the same time, the backdrop of professional wrestling images creates a free associate and enigmatic narrative within the photograph. For me, at the forefront of this narrative is the tension between the inaccessible boyhood fantasies of wrestling and repetitive bodily activities, like pumping a soap dispenser.

You have worked with your mother and father in many of your videos and performances. Do you feel that they are actors or props in your work, or do you view them as collaborators?

I think of my parents as collaborators, but with a distinct hierarchy in mind. In my performances from the past few years, my parents’ actions were very controlled and choreographed, and often they did not move at all. In two of my most recent performances, I allowed their actions to be more casual and self-determined during the actual performance. This was in contrast to the very controlled and pre-determined actions I was carrying out. This contrast created a sense of ambiguity between what was actually the performance, and what was just my parents living out their lives in front of an audience. One would wonder if my father was being my father, or being a performer playing my father. In a way, he was being both. While I am still interested in creating still, tableau vivant performances in the future, I will further explore this relinquishing of control in my upcoming performance at Horton Gallery on February 5th.

*To learn more about Bryan’s personal history, click here to view a comic strip timeline of his life by comic artist Eric Winkler.

(Images courtesy of the artist)

RSS

RSS