At the risk of generalizing, I’ll admit that I am often suspicious of art that presents itself as “conceptual.” What frightens me is the disconnect that often exists between concept and experience. Discussing this idea with an acquaintance at a party several years ago I was asked mockingly “do you seek to be moved?” I do, and firmly believe that successful conceptual art can elicit not only a cerebral, but also a visceral physical response in the viewer. With this in mind, I had few expectations when I wandered into Sean Kelly Gallery in Chelsea last Wednesday. What I found was a mixed, but ultimately satisfying exhibition of works by Joseph Kosuth.

The first two installations present relatively standard fair in terms of Kosuth’s oeuvre. There is a recreation of the artist’s first gallery show in 1968. The ten photo works on aluminum present his famous black and white dictionary definitions of “nothing”. While the pieces might be slightly obsolete on their own, the pleasant scent of nostalgia hangs in the air to good effect. A neon installation based on James Joyce’s Ulysses from 1998 was on display in the next room. This installation was perhaps less impressive considering the glut of uninspired neon at this years Armory show. Having said that, it would be foolish to discount Kosuth’s early and frequent mastery of this medium.

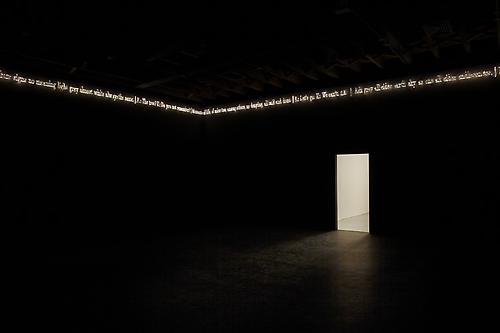

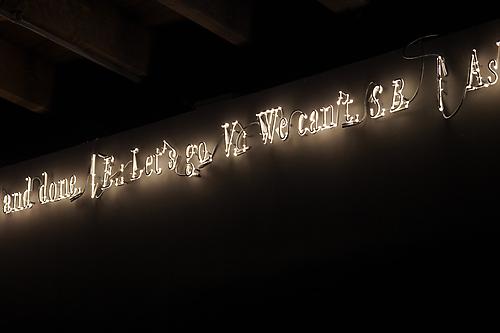

The main gallery features an ambitious, never before exhibited work. The cavernous space has been transformed into a black walled void. A single band of neon spells out excerpts from Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and from his lesser-known Texts for Nothing. Hovering just below the ceiling, the author’s words are eerily disembodied from their surroundings. The muted light only emphasizes the thick sense of blackness oozing through the room. The only sound is the hum of electricity. The artist is undeniably present, contemplating the void from dimly lit margins. The result is both disquieting and meditative. I circled the walls of the gallery four times before realizing it. As I stumbled through Kosuth’s amalgam of borrowed language I felt my stomach tighten. What I encountered was the punch in the stomach I have been waiting for. Kosuth’s strength plays expertly in the space between meaning and its presentation, and Texts (Waiting for-) for Nothing’ Samuel Beckett, in play, is no exception.

RSS

RSS