George Condo was born in 1957, meaning he is 53, the same age as my mother.

The artist’s newly opened retrospective “Mental States” at the New Museum, was exceptional in part for this reason. It was refreshing to see an exhibition of this weight and vitality at the New Museum. It was especially exciting considering the artist is not “younger than Jesus” but 4 decades into his mature career.

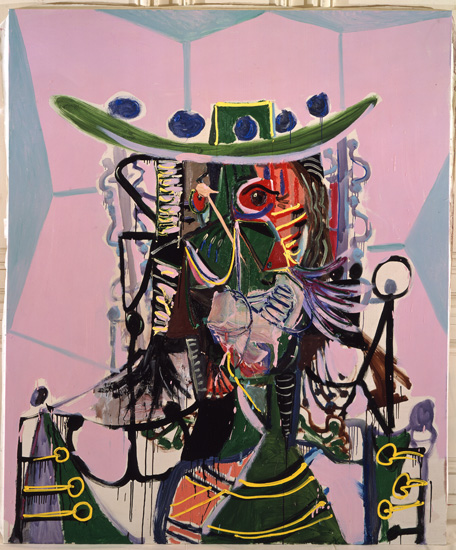

At the risk of seeming vague or trite, or both, there is something timeless about George Condo’s Work. During the 1980s, while friends like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and Mary Heilmann were developing their own signature styles, Condo wasn’t. Rather, he was constructing his toolbox. The artist has become a master of appropriation, not of material but of style. He has an uncanny ability to pull inspiration and support from across art history. An avid museum visitor, the artist constantly footnotes artists as disparate as, Picasso, Bacon and Fragonard.

Mental States begins in the cavernous fourth floor gallery, the back wall is plastered with paintings. Hung in the classic salon style, one gets a sense of the history with which Condo plays. Here, accompanied by a strong dose of wry humor, are the cubist-esque jumbles, the Bacon inspired anguish, and even the brown soup of a renaissance style portrait background. Rather than feeling disconnected, the display unifies. Each painting functions, as a unique facet of the artist’s idiosyncratic, and ultimately rewarding oeuvre.

Downstairs, on the third floor, the exhibition is broken up into three galleries, loosely organized by theme. The first room, labeled “Melancholia” is home to a group of particularly forlorn couples. I was particularly struck by the characters depicted in “The Stockbroker”. Awkward and misshapen; the strain of Condo’s cartoon subjects is almost palpable. The next room, “Manic Society” is almost a relief, though the bacon-esque contortions of these paintings are hardly cheerful.

The last room is a testament to the artist’s ongoing relationship with abstraction. “Black and White Abstraction” from 2005, is a particularly aggressive reference to de Kooning’s black and white paintings from the 1950s. At first glance, this and the other paintings in the room seem masterful exercises in gesture and tone. Upon further examination, the languid cartoonish drawl of Condo’s figurative vocabulary begins to reveal itself, one eye, nose and face at a time.

This is what is so wonderful about the artist; there is a fantastic tension in each painting. Subsumed in a variety disguises, it is only after real examination that the artist begins to emerge, peeking out from an imagined past.

RSS

RSS