It is hard to believe that the 1913 New York Armory Show took place less than 100 years ago. The seminal show drew laughs for its paintings and denunciations for their degeneracy, while the medium of photography, facilitated by Alfred Stieglitz, was inaugurated as a new art form, acceptable only as measured by proximity to the extreme paintings and sculptures on exhibit.

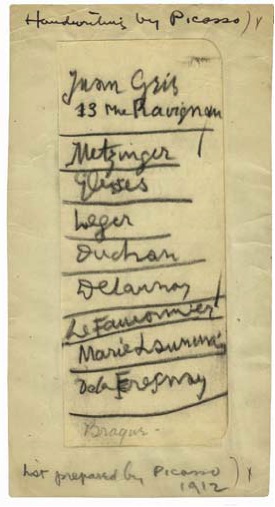

It is Picasso’s list of suggested artists for inclusion in the show, dated 1912, that makes a case for the subtleties that make this Morgan sleeper, “To-dos, Illustrated Inventories, Collected Thoughts, and Other Artists’ Enumerations from the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art”, a must-see for anyone interested in art history or contemporary art or both. Through curatorial acumen, its 80 lists simultaneously remind us how different yet familiar at the same time the world is today from the one reflected in the exhibit.

With tweet-like efficiency, Picasso’s list of recommendation includes the names of Gris, Leger, Duchamp, Delaunay, and Metzinger for inclusion in the show at the behest of organizer Walt Kuhn. It is as prescient and powerful as a manifesto and staggering in its significance, considering the impact these names would have in ushering in the era of abstract art in America. Moreover, the art market in New York City, which currently boasts hundreds of galleries, was virtually non-existent. Considering the paucity of galleries in New York City at the time, whose numbers would rise to only forty by the time WWII began some 25 years later, the impact of abstraction, to this day, remains unequaled.

Pablo Picasso, “recommendations for the Armory Show for Walt Kuhn, 1912

Consider Joan Snyder’s response to the question “What is Feminist Art?”, written in 1976 as part of an art project. It starts “Feminist sensibility is…” followed by a three page list of nouns. Included are anatomical terms, art supplies, constituents of the art world, and short rants against dominions of the art world interspersed with action words in a brew-ha-ha befitting the challenges and frustrations of women artists contending with “piece of the pie-ism.”

Or Grant Wood’s list, written in 1931, of 14 “business” depressions between the years 1819 and 1931 with the closing comment after 1931 (and 1932) that “all came to an end except this one. Mebbe this will….” Maybe readers will find this too painful to contemplate outside the context of art reviews.

If R. David Lankes, Director of the Library and Information Science Program at Syracuse University is correct about knowledge being a process, this show illustrates why the digital environment is merely a tool for acquiring knowledge and not a repository of knowledge itself; that knowledge “is what we do and why we do it, not something that can be boxed up, transferred, or archived.” Reviewing Joseph Cornell’s list of purchases at the Madison Square Garden antiques fair in 1957 are found “a set of cards (picked from broken lot) of characters in various amusing scenes, miniature toy wagon, horse and driver, German ca 1900, and misc marbles (marked as sold).” Readers familiar with the artist’s work will invariably find themselves imagining the resulting assemblages with each tick. These lists are so much more than keywords on a screen.

RSS

RSS