Pace is an art gallery synonymous with New York City. Having moved here in the 1960s from Boston, owner Arne Glimcher has built it into something of a dynasty. This September marks the gallery’s 50th year in existence. To celebrate, Glimcher has organized a massive exhibition sprawling across all four of his Manhattan gallery spaces. The show features influential and important paintings from across Pace’s five decade history. The uptown space has been organized into a mini retrospective of notable Pace exhibitions. The other three spaces in Chelsea are ordered based on a rough chronology, featuring contemporary art, abstract expressionism and pop art, and “minimalism and post modern art” respectively.

For those who have visited Chelsea lately, it’s been impossible to ignore the fleet of banners announcing “50 Years at Pace”. For all of the advertisements and press coverage, one could be forgiven for mistaking the exhibition for a major museum blockbuster. In a way perhaps that’s what it is. Glimcher certainly pulled out all the stops, securing loans from private and public collections including MoMA, The Whitney Museum of American Art and the Tate in London. That he could secure these high profile loans speaks to the gallery’s influence. The exhibition is a catalogue, not just of art, but a visual history of the relationships fostered between Pace and successive generations of artists. To view the multitude of famous paintings and sculpture is to understand the gallery’s storied history.

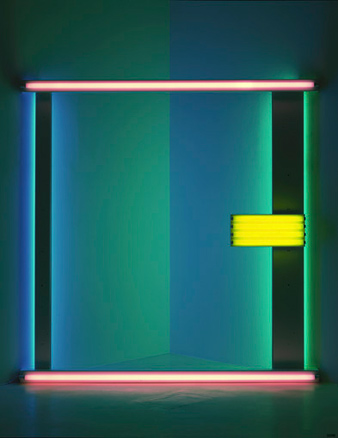

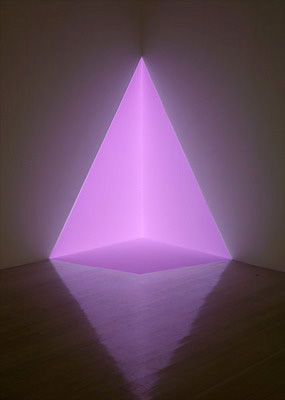

Having said that, this show was a confusing disappointment. Everything is there, no expense has been spared. On 25th street my jaw dropped as I stood in front of a wall sized Clyfford Still from 1956. This painting belongs to the Whitney, and seldom sees the light of day, which is a shame. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to stand, mesmerized in front of the looming blacks, and pulsing, jagged reds of this canvas. There are also canvases by Rothko and Pollock. On 23rd street, a breathtaking group of works by Dan Flavin whisper across the gallery to an amazing installation by James Turrell. Unfortunately, these amazing works, and others just as notable get lost in a confusing jumble. Room after room, decade after decade, I began to feel as if I was inside a trophy case. There was no cohesion, no dialogue, and no nuance. Sections of work did not support each other but felt obvious and clumsy.

Though the exhibition amounted to a confusing “greatest hits” it wasn’t all bad. In fact, the show was quite enjoyable once I stopped treating it as a narrative exhibition, but focused on individual groupings of work. I tried to imagine the work on each wall in a separate booth, perhaps at an art fair. All in all I suppose I appreciate the exhibition. Pace has brought a wealth of beauty, which is often locked up in storage, back into the public realm. For that alone I am thankful.

RSS

RSS