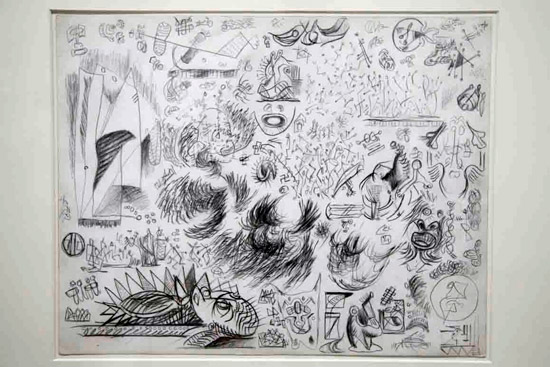

Upon entering the MoMA’s Abstract Expressionist New York I immediately felt at home. As cliché as it may sound, MoMA’s most recent exhibition, which takes up the entirety of the fourth floor painting and sculpture galleries, is full of old friends. The show combines hundreds of paintings, sculptures and works on paper from the permanent collection, in an exhaustive effort to showcase New York postwar painting. Many of the paintings in the exhibition are gems usually on permanent display. Re-configured into a new narrative structure, the exhibition has shined new light on old favorites. Barnett Newman’s The Wild, Jackson Pollock’s Echo: Number 25, 1951 and Franz Kline’s Chief are among the most iconic of these examples.

When I heard news of this exhibition, I couldn’t help but think “here we go again”. Since its critical acclaim in the 40s and 50s Abstract Expressionism, and its attendant art historians and critics have been exhaustively revisited, re-imagined, and critiqued. Though most of what has been said is true, to launch an exhibition from this era is now, indeed a daunting task. Several notable critics were quick to lambast the show. It is true, all the big names are there, large rooms are dedicated entirely to Pollock, Rothko, and Barnett Newman who have long dominated the spotlight of this age. It is far from the revolution I know many critics, and art lovers would have liked to see. If not a revolution “Abstract Expressionism New York” is progressive and sensitive. While much of the fourth floor has been dedicated to the art of eight or nine of the most famous artists of the generation, there are paintings and sculptures by lesser known painters. While the exhibit doesn’t address the exclusion of female and minority painters, it does include examples of both. Works on paper and canvas by sculptors like Herbert Ferber and David Smith are also on display. Though far from perfect the broad scope of artists, mediums, and works in this exhibit make it a must see.

RSS

RSS