Last winter I stood on a cold subway platform and told Y about my new crush: David van der Leer. “Who is he?” she asked, distracted. She was peering down the dark tunnel, hoping to see train lights headed our way. It was one of those very snowy late nights in New York, and we had fallen victim to the slow timetable of weekend trains. I don’t know, I said. Some curator at the Guggenheim. Y turned her gaze on me. “You don’t even know who this dude is?” she asked. I shrugged and told her I liked what he’d been curating. She shook her head. Who falls for someone’s curation?

In van der Leer’s case, lots and lots. Google him and up comes one article and interview after the other profiling either the assistant curator himself or the shows in which he’s had a hand. The man has fans. That’s how I came across van der Leer—reading an admiring write-up about the Frank Lloyd Wright show he’d assisted with and then later when I was researching Futurefarmers, a San Francisco-based art collective he brought to New York last spring. Then, one warm, rainy night last June, a friend and I happened upon Pedro Reyes’s Sanatorium, the first in the stillspotting nyc series van der Leer oversees. The pop-up exhibition was held in a high-ceilinged storefront in MetroTech—that curious, liminal area of downtown Brooklyn—and it featured men and women in lab coats offering spiritual and physical ministrations beneath fluorescent lights. The severe sterility of the space recalled hospitals, a nice counterpoint to the typically warm and busy aesthetic of New Age therapies. (Think here of the myrrh-scented, cluttered woo-woo shops along Bleeker, and you’ll know what I mean.)

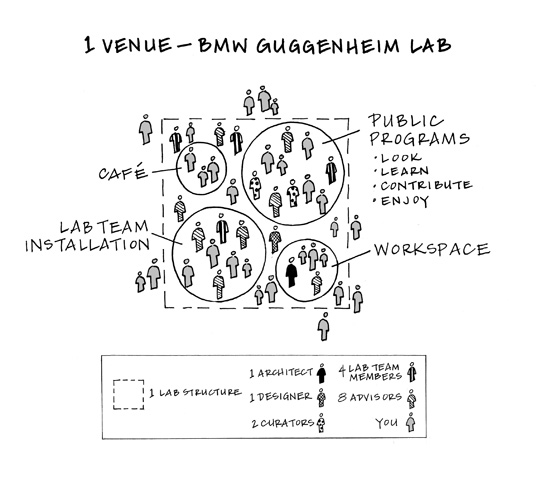

Like elements of the Futurefarmers exhibition, stillspotting nyc roams outside of the Guggenheim’s famously curved walls. The transient and mobile quality of the installations is replicated in the BMW Guggenheim Lab, an ambitious, multidisciplinary arts showcase that will travel to nine cities around the world in six years. It launched in the East Village last fall, when the public could choose from myriad happenings—lectures, block parties, tours of toxic sites—offered by the lab, which claimed “comfort” as the topic under its microscope. It next travels to Berlin, where the lab will appear in a different incarnation in May. (Plan ahead now; Berlin is lovely in the spring.) Stillspotting nyc also continues apace this spring, extending the migratory reach of the Guggenheim, perhaps one of the most exciting aspects of van der Leer’s curation thus far. I spoke to him about his efforts with the lab, which he co-curates with Maria Nicanor, and his curatorial approach and found out why so many find the curator worth profiling.

CL: Why did you choose comfort as the first topic for the BMW Guggenheim Lab to study?

David van der Leer: We were looking for themes that are slightly emotional, that people can respond to without having a big knowledge of the themes you would normally associate with cities. Domestic space is usually related to comfort, so when people hear “comfort,” they immediately think of a fluffy bed and all that kind of stuff, but not necessarily about what comfort means in a city. If we ask people very specifically what’s “comfort” in a city context, they usually respond, “Oh yes, a park along the river,” but what does it mean when you start to confront those notions?

CL: Tell us about where the lab will be traveling.

DvdL: It’s important for us to go to bigger cities and cities all around the world. Smaller cities are also interesting, but I think that’s a different project. For instance, I’d love to do a project on suburbia, but this project is built to look at metropolises around the world. Berlin is a little smaller, but, all in all, they’re quite big cities.

________________________________________________________________

“I think as soon as you take something out of the museum and place it in an urban context, it becomes a very different animal. It becomes something that people can respond to … If we had done the same installations at the museum, it would have been impressive but not as effective.”

________________________________________________________________

CL: How do you think a larger city versus a smaller city or the different regions informs the themes of each two-year cycle?

DvdL: Some of the bigger issues in cities, such as transportation and housing, become a little more sharp in even bigger cities, so that’s why it’s interesting for us to look at the biggest places. I think it will differ from city to city and will be based on what the lab team does. In New York, it was fairly abstract because the team decided to look at the city as a system. In Berlin, it will be a very different project, much more practical. Also, the public programs around it will shift and change.

CL: Urban issues seem to be of programmatic interest for curators. There was the Global Cities show at the Tate Modern in 2007 and last year the Festival of Ideas for the New City organized by the New Museum. Why or how are urban issues a curatorial concern?

DvdL: One of my frustrations if you look at this type of show is you get a lot of photography. You get a lot of diagramming and maps, and they give you a sense of the reality of cities. They almost want to say, “Okay, we understand the city,” whereas I think the complete opposite. All of those tools are very valuable and helpful, but I don’t think we understand cities at all.

I think it’s important to approach it from another end, which is why we created a project that was much more about people than about the data that’s all subjective anyway. We created a project where people would be the core element of all the conversations, and at times there are poetic moments.

CL: What makes you say we haven’t figured cities out?

DvdL: I don’t think we can know what a perfect city is. We know how to create utopias on paper, but utopia has never materialized. You get driven by how a city is organized, and here especially the grid system creates a fairly anxious city. You never stop. It has to do with city form and the organization of cities.

CL: You mentioned poetry a little while ago, and you’ve referenced it in previous interviews. The poetic or lyrical seems to be valuable to you. How does it show up in your curation?

DvdL: I think it’s nice when things aren’t necessarily catered to a conclusion or an answer. I like it when projects are more layered, and people need to find their way through it. It’s basically way-finding, which I think happens with the lab, as well as in stillspotting. Futurefarmers, too. You run into things you may not have expected. That can be fairly poetic.

CL: Why is way-finding a preferred approach for you, and what do you think it offers visitors?

DvdL: Everything is so direct in how we live our lives that, for something to really have an effect, you sometimes have to do the opposite. More intriguing can be super effective. For instance, with stillspotting, we’re running two years of programming on stillness around New York. Normally, you would start off with numbers—”Noise is bad for this reason”—and we’re using that type of language, but we’re trying to get people to go to one or three or perhaps all of them and realize, “This is something I could find myself, too, without necessarily having to make drastic changes in my life.”

CL: You’re so focused on the internal architecture of the visitor. Can you speak to that?

DvdL: Things can be so, so direct. It’s fairly easy to get people to have an emotion, but these projects are less direct in terms of information. They can go to the core in a different way. For instance, with stillspotting, I could’ve made a show with fifty objects all nice and beautiful, and it would’ve been a nice and quiet show. But I think as soon as you take something out of the museum and place it in an urban context, it becomes a very different animal. It becomes something that people can respond to. In the museum, it becomes abstract. If we had done the same installations at the museum, it would have been impressive but not as effective.

CL: How do you judge effectiveness?

DvdL: Getting some emotion out of people. When you’re emotional, it’s sometimes easy to learn something, and that’s something we’re trying to get at. People respond very positively and sometimes very negatively, but I like that there is some sort of response to things. Otherwise, the type of show you referred to earlier is important and interesting, but it’s very difficult to respond to it. You pick up some information, and that’s usually it.

CL: So how would you advise someone interested in becoming a curator?

DvdL: I’m the worst example actually, because many curators are probably art historians and often know for a long time that they want to be a curator. I’m trained in urban and architectural theory and then worked for architects and ended up here not entirely by accident, but it was some sort of accident. What I’m trying to say is for some curators there’s definitely a path and it’s very logical, but it can have a little bit of a twist.

CL: Right, you don’t have the same perspective.

DvdL: Well, I share many of the same perspectives, but I’m less driven by objects. In many cases, curators are forced to think about objects. That’s the nice thing about our projects. They’re either about discussions or emotions, and often an object is a part of that but it doesn’t have to be so romanticized.

_______________________________________________________________

Cielo Lutino is a Brooklyn-based freelance writer and editor covering culture, urban, and technology topics for clients including Econsultancy, NYU-Polytechnic Institute, and Bloomberg Businessweek, where she is a weekend editor.

_______________________________________________________________

All images courtesy of The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

RSS

RSS