At the heart of the interdisciplinary, experimental approach to art making documented in “Black Mountain College and Its Legacy” at the Loretta Howard Gallery, is a human ethology that emphasizes cooperation and interdependence. What happened at Black Mountain College is as nostalgic as it is antithetical to western society’s preoccupation with the importance of the individual over the group, most recently highlighted with the passing of Apple’s visionary icon earlier this month.

In an early 20th century America, the maverick North Carolina-based institution fostered a breadth of inter-media (multimedia) projects achieved through assemblage, a style of working Steve Jobs would never have subscribed to. Therein is this show’s value and significance. It is a celebration of creativity achieved through mutual dependence versus the aggression and competitiveness our society often celebrates in our (now post-Jobsian) world.

Picture a college campus populated by some of the greatest artists and thinkers of the 20th century, including Buckminster Fuller, Ben Shahn, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Harry Callahan, Dorothea Rockburne, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage, many of whom have their work on display here. Yet, Black Mountain College was not an arts school, although there are over 100 works by 35 artists in the show. It was a liberal arts college (it closed in 1957) that experimented with art.

. . it really became kind of recognized [at BMC] that art could be anything, and could be made out of anything, and that it didn’t necessarily cross boundaries — they thought – between theatre, the visual arts, dance, music, etc., that you could mix all this up and make a multi-media – or . . . environmental art.

Kenneth Noland, Student 1946-48, 1950 Summer Session

Robert S. Mattison, who co-curated the show with Ms. Howard and wrote the catalog, offers several insights about the visiting artists’ program which differentiated the college. “BM stands out for freedom of inquiry. Artists were invited without institutional restrictions, and the interactions with the students were determined almost wholly by the artists themselves…[it’s] heritage is defined by the linkages between individuals.”

“Black Mountain College and Its Legacy” challenges viewers to consider what resulted when the talents of so many innovative artists from such a variety of disciplines were harnessed in a remote valley setting just outside of Asheville between 1933-1947. The show gets an aural jump-start with John Cage’s debut into electronic music, Williams Mix, 1952-53, which is analogous to techno-rock today. The sound piece is followed by a photograph of David Tudor’s performance of Cages’ “4’33”. To learn that Cage credits Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings as the inspiration for the piece is to begin to understand how the dots connect within the context of the expansive two-storey show. Around the corner is Merce Cunningham’s film Antic Meet, four short filmed “studies” of the roots of modern dance, tedious because our awareness of the dance that would follow it is now mature.

Dates on many of the works place the artist’s career on a continuum between those influenced by the “legacy period” and those made more recently. Willem de Kooning’s Standing Figure, c. 1948-50, for example is shown next to Two Women, 1963. Kenneth Noland’s 1949 V. V. is next to the 1963 Soft Touch. Ray Johnson’s hypnotic collages include Untitled (Dear Suzi) 1958 next to 3B (Back of Cupid Head with Snake) 1992 with Untitled (Merce Cunningham) 1982-88 wedged in between. In the later work, Johnson sums up why Black Mountain matters; embedded in the piece is written: after 40 years of avant-garde choreography, the grand old man of experimental dance is still treasured by the young and finally winning mainstream recognition.

Dorothea Rockburne, inspirational in making the show happen in Chelsea, contributed Gradient and Field, 1971. The piece further exemplifies an interdisciplinary approach and employs set theory, introduced to her by mathematician Max Dehn who spoke to her about “mathematics for artists”.

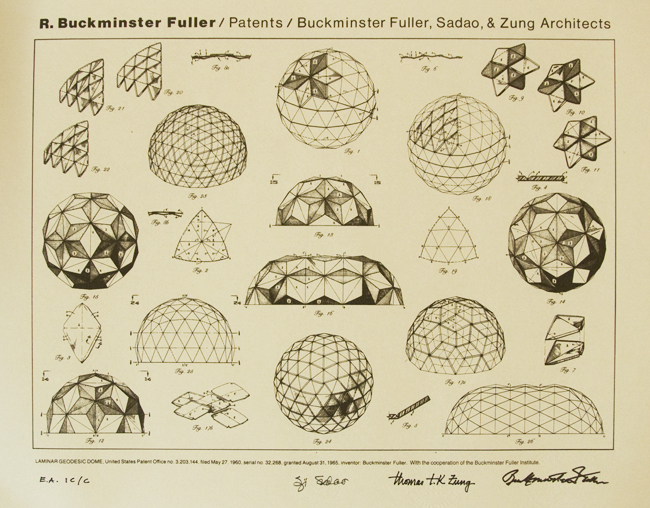

The story of Buckminster Fuller’s mobilization of the BC community to participate in building an unsuccessful prototype of what would later become the Geodesic Dome illustrates his inspirational mantra, “everything is connected”. This is demonstrated in a photograph of students raising the failed Supine Dome above their heads, by Beaumont Newhall. Newhall would later become curator of the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House from 1948-1958. A schematic print of Geodesic Dome accompanies the group shot, again, connecting the dots, or in this case, the venetian-blind material used to construct the Supine Dome. Closest Packing of Spheres, 1980 proves to be a more concrete time capsule than the ephemera on the wall, but not less thought-provoking.

Where Jobs practiced control, Black Mountain eased it, erasing boundaries between who teaches and who is taught as well as the differences between dance, geometry, sound and the line—a legacy worth knowing about.

RSS

RSS

It’s where it stared…

October 30, 2011 @ 5:32 pm

GR, thanks for this great post. great meeting you at The Public yesterday. -RL

January 16, 2012 @ 7:58 pm