In the bath (Mother and sister) 2009

Clarisse d’Arcimoles is a 25-year-old French artist living in London. Her work can be found at Saatchi Gallery until April 30th as part of NEWSPEAK: BRITISH ART NOW and in Tel-Aviv at the Alfred Gallery until April 31st. A solo show in London just closed at Degree Art Gallery and she had a busy 2010. BOOM! That’s Miss d’Arcimoles blowing up – and rightfully so. Her powerful images and projects bring to mind a dozen other positive adjectives. The power in her work partially lies in the multiple jumping off points for the viewer. You’re viscerally thrown off guard with emotion, intimacy, humanity, and history. Artcards Review digitally jumped the pond to talk with Clarisse.

Brent Birnbaum: Let’s start with the Market Estate Project. A year ago a council estate with 571 flats was bulldozed in Holloway, North London. Up until its final days, 31 families still called the Market Estate their home. Some residents had for over 40 years. This complex built in the 1960’s represented a utopian vision of modern urban planning. Were you familiar with the building prior to discovering it was going to be leveled?

Clarisse d’Arcimoles: We were seventy-five artists who had been granted the possibility to work on site, to transform flats left behind, corridors, staircases, building facades and change the estate into a creative playground, knowing all along that market estate would be demolished. Surprisingly, I was the only one who really built a personal relationship with a resident. It is probably due to the fact that Jimmy Watts was one of the few who didn’t want to move out and leave all his souvenirs behind.

BB: At what point did it hit you there was an art project to be had here?

CD: The first time I came I could only see the gloomy and desolate sides of it. It was hard to believe that there were still people living there. I started taking photographs and I was really intrigued by the building itself at first and eventually more so by the abandoned flats. I also started researching the history of the estate but it is only the day I entered for the first time in Jimmy’s flat that I realized there was an art project to be done. In the end, Jimmy by sharing his stories was the only one who really made me understand how alive and lovely this council estate used to be. This was something I wanted to share with the audience from the really beginning.

BB: Jimmy Watts was one of the first residents to move into the Market Estate, which occurred in 1967. How did you approach him? Was he receptive to your artistic ideas from the beginning?

CD: I met Jimmy on January the 15th. He was standing next to the lift and was carrying a shopping trolley. He was mumbling because the lift was broken so I asked him if he needed help. He introduced himself saying that at 87 years old, he was the oldest resident of the estate and had been there the longest. Five days later he invited me for a tea in his flat. I noticed the pictures on the walls, which were already gone and the traces of them still visible. Jimmy spent forty-three years in this estate, as he told me later, and was forced to move, leaving his memories behind. I stayed with him all afternoon listening about his souvenirs; each tiny object was a reminder of passed times. Jimmy was aware from the start that I was doing an art project about him however at that stage the only important thing was for him to have someone to talk to and tell how much he used to love this place.

BB: How did the other residents react to you focusing on Jimmy?

CD: I never really met or spoke to the other residents and I was very lucky to have met Jimmy who had so much to tell. He had seen the estate from its birth to its demolition. To knock on his door and enter his flat was like time travel for me. By the end of the project, I realized I had not even spoken to any of the other 74 artists working on site on other projects for almost two months.

BB: Mr. Watts opened up his life to you. I imagine there were some intense moments. Imaging this through your simple yet profound presentation of the project is highly charged. Were there any times either one of you were overwhelmed with emotion?

CD: Jimmy’s whole life in the estate was packed inside sealed boxes. It all eventually came back to life the day he opened one of those boxes to share his super 8 home movies with me. I discovered wonderful moments of Jimmy’s life. One of them his son, as a boy, is dressed as a magician, performing simple tricks by making the most of the camera. In reality, the boy pauses the film and removes a cup from the table, making it look as though it has disappeared. The images on the screen of a happy, thriving estate, a hive of activity in an exciting modern setting, reflect some of the utopianism of the estate’s first residents. The discovery of those fragments of life hidden in those boxes for three or four decades from what Jimmy calls “the good old days” was magic. I could see the places and the faces being brought back to life, he said “I shall treasure these images forever”. We both laughed and felt at that moment so vulnerable and fragile. A week later I received a call from Jimmy asking me to accompany him to visit the new flat he was forced to move into. He was going there for the first time. We discovered that his new flat was facing the old clock tower, which was a landmark of the Market Estate. He whispered to me that every time he will look at it, he will remember. That day we both felt a little lighter.

BB: How did Jimmy Watts feel being the subject of an art project as things began to develop and he could see what you were creating?

CD: Each time we met, Jimmy would surprise me by sharing so many memories and records of his family life. He also showed me some old newspaper, which traces the history of the estate but also explains its rise and fall. It is only the day he moved out of his flat and gave me the keys that it really felt to both of us that he was the subject of an art project. I spent one week working alone in his empty flat, my feelings were fluctuating between nostalgia, having spent all these days with Jimmy in those rooms and excitement at the idea of offering him a beautiful homage on the day of the event.

BB: It has been a year since you did this project. Are you still in touch with Jimmy?

CD: Absolutely! Jimmy sees me as the daughter he never had. While for me he has somehow replaced my Scottish grandfather to whom I was very close. Next time I see him, I will definitely print this interview and show it to him. He is so happy and proud. It is my way of saying thank you to him.

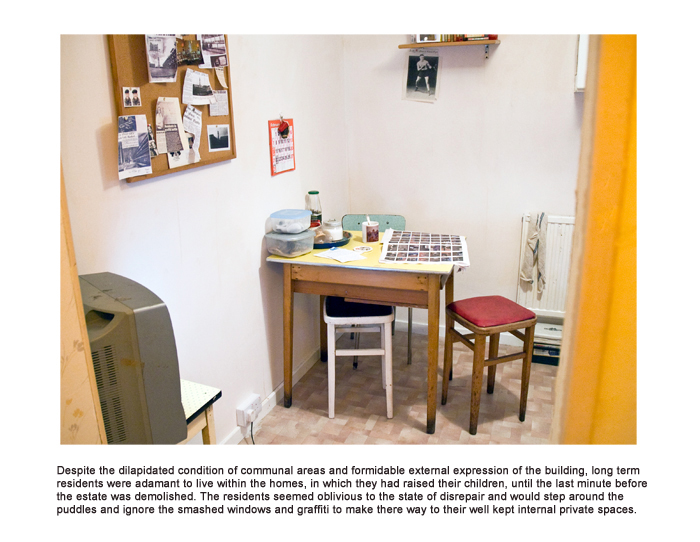

BB: Your collaborative installation, The Rise and Fall, faithfully and meticulously re-created Mr. Watt’s kitchen within the white box of a gallery. Did Jimmy Watts attend the exhibition? If so, how did he react?

CD: Unfortunately he wasn’t able to, although I did my best to convince him to come. In a way we are all similar. It is so hard to leave a place because we are scared of forgetting, and once we leave we don’t want to go back out of fear of remembering.

BB: You have also exposed some intimate moments within your family. Let’s discuss your artistic process with the Un-possible retour project – which has received a lot of well-deserved attention. In this series, you recreated decades old photos of family members. The original photo is shown alongside the new photo. Seeing the aging of a person, as the background more or less is the same is staggering. There is some fully accessible art mojo here. How did this project dawn on you? Furthermore, did you always have this collection of family photos, or is it something you pieced together at your parents house back in France?

CD: The initial inspiration for wanting to do this project came from a photograph of my brother and I when we were very young, having a bath together in a small pink bucket. I produced Un-possible retour as my graduate project. I had three months to produce the work and it is only when I went back to my parents’ house and looked carefully through my family albums that I realized how difficult and ambitious this project was.

BB: Specifically dissecting one work from the series, In the bath (Mother and sister), some small bottles appear on the bathtub edge beside your mother’s head. Why did you decide these should be in the new photo, as nothing was in that spot in the original photo?

CD: The problem when you shoot a picture in a bath in the evening and the five members of your family already had a shower, there is no more hot water! In the rush we simply forgot. I could have removed them afterwards on Photoshop but I like to leave room for doubt.

BB: We see the inevitable aging of housing complexes and people in your projects. Your attraction and even possible fascination with time is evident. I read you see time as a collaborator. This brilliant notion is something people push against their whole life, yet you seem very accepting and embrace time. Has this been an interest of yours since you were a child or has this progressed as your interest in Photography has?

CD: I started questioning myself a lot to understand why my relation with time is so intimate at the age of 25. I suppose that I am too young to use it as something hostile or fatal so I use it as collaborator. I find it fascinating to experiment with the ability of photography to play with the time and manipulate it.

BB: I recently saw one of the best works of art in New York I have seen in years. Did you see Christian Marclay’s work The Clock when it was at White Cube in London? If so, give us your thoughts as it is all about time.

CD: For the one who lives in London and missed it when it was projected at the White cube, you’ve got a second chance to see it at the Hayward Gallery at the British art exhibition!! It is an outstanding idea, totally captivating and amazingly well thought out. In this artwork you could either forget about time while you are constantly told what time is or you could end up feeling that you’re wasting your time just by watching the passage of time. It reminds me the work of Candice Breitz, which also manipulates film and music, remixing familiar footage into epic narratives.

BB: Onto my standard ending questions. Are there other artists whose work your excited about or other people you would cite as influences?

CD: I am totally addicted to Sophie Calle’s work. I admire her madness and the simplicity in her presentation. It seems that for her being an artist is an excuse to explore her boundaries and do things she wouldn’t normally do. I also love her unique way to tell us stories.

BB: The projects we discussed seem conceptually and physically time consuming to construct. Are you brainstorming any other big projects or have a mental queue of work in your head you care to share?

CD: Brainstorming! That is exactly where I am at the moment! This new project began the day I decided to look through old photographs of strangers. I found a lot in second hand and antique shops, and discovered entire lives documented. One that particularly struck me was a 1940’s photo album that showed a young man from birth to the last day he was seen by his family, the day he left to fight in World War II. So far it is the story of an unknown soldier.

BB: Finally, what are you working on right this second (besides this interview)?

CD: I spent my day gardening, and while I was gardening I was thinking.

Artist Website:

clarisse-darcimoles.com

RSS

RSS