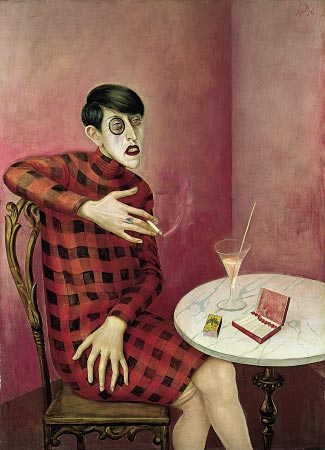

The first U.S. exhibition of German painter Otto Dix, at the Neue Galerie is long overdue, and after a recent visit, I have discovered a newfound admiration for a painter whom I only thought of as creating Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden. This exhibition proves Dix to be an incredibly self-aware artist who dedicated his life to the study of painting, and in turn, the study of the human condition as seen in his many variations on portraiture. The exhibition at the Neue Galerie begins with a small gallery full of his work made during World War I, a body of work that ultimately sets the tone for his entire artistic career.

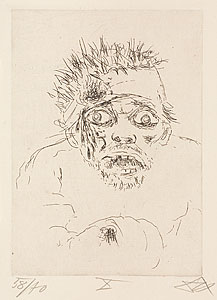

The series of etchings from the War/Der Krieg portfolio bring to mind the lithographic work of Mexican artist, José Clemente Orozco. However, instead of images of impoverished, displaced families during the Mexican Revolution of the early 20th Century, Dix spent years documenting the horrors of World War I in Europe. In these series of etchings and drawings, Dix’s line quality and use of chiaroscuro renders his style strikingly similar to Orozco, even though they were an ocean apart. Even stronger than the similarities between Dix and Orozco are the similarities to Käthe Kollwitz’ various print portfolios. Kollowitz spent the 1910s and 20s documenting how suffering families, women and children, were affected from the war, whereas Dix, as a soldier for the German army, was out on the battlefield. These earlier works, made from 1914-1918 (not printed and published until 1924) are not illustrative to those works that Dix is most known for: portraits of the haute-classe or bourgeoisie of the Weimar period. Rather, these drawings and prints are firsthand reactions to the horrors surrounding the artist during the War. It is important to realize that these scenes are not fantasized images that one might see or dream up from a horror movie or novel, but almost diary-like accounts of a typical day in a soldier’s life in WWI. Especially horrifying are the gruesome portraits (can I even call it that?) of war victims. In the drawing of Wounded Veteran/Kriegsverietzter, Dix adds shock value with red watercolor paint to illustrate the horribly disfigured right side of the man’s face. Skin Graft/Transplantation shows the revolting effects of hurried surgery, and Wounded Man Fleeing (Battle of the Somme 1916)/Fliehender Verwundeter (Sommeschlacht 1916) shows a man more terrified than terrifying; his fear transforms him into a Gollum-like, monstrous creature.

After the war, Otto Dix moved to Dresden to continue his studies at Hochschule für Bildende Künste, launching a lifetime career in painting. Although he was out of the trenches and off the battlefield, Dix still seems to have always carried a feeling of disgust towards humanity, as all subjects in his future paintings retain a disfigured or inhuman quality. Some of his portrait studies of women are as appalling as the men in war. The woman in Head I – Mrs. D (Head of Woman I)/Kopf 1 – Frau D. (Frauenkopf) (1923), smiles sheepishly, but her face is lost in a haze of reddish-pink smudge, making her blue eyes brighter and bigger than normal. The Half Nude/Halbakt (1922) is an ogress of a woman, her face more baboonish than human. The woman in Rachel I (1924) has blue lips, grey skin, and appears corpse-like, and the Old Woman/Alte Frau (1923) is simply just a drawing of a skeleton with wisps of hair. In the following gallery, Even Dix’s later studies of the circus and other realms of the world of entertainment continue to portray corruption, illness, and hysteria.

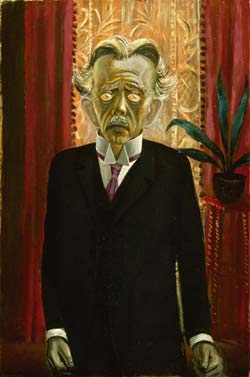

During the Weimar era, Otto Dix became most well known for his portraits representing the varied types of people during this time period in Germany. It is during these years that Dix’s use of color develops into full force. The sitters’ cheeks are a drunken rosy red, their eyes are popping blue or shining brown, and the backgrounds are washed in deep ocres of a curtain or the soft periwinkle blues of the evening sky. Disturbingly, one thing that remains constant is the pale, white face on almost every portrait.

Dix took his own liberty in deciding how he wanted a person to look. He was certainly deeply affected and troubled by his years serving his country in World War I, as his subjects never really return to human forms. Although Dix accurately captures the roly-poly shape of a man in Portrait of the Laryngologist Dr. Mayer-Hermann (1926) his shoulders are so disproportioned that his body turns into a full spherical shape. It is impossible that the seductress in Reclining Woman on Leopard Skin (Portrait of Vera Simailowa) (1927) had a face so felineness. And Dr. Heinrich Stadelmann (1920) has outrageously large ears, nauseously green skin, and bulbous, protruding pink eyes.

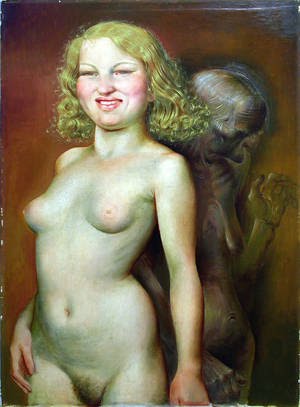

Dix continued his studies far and wide, and was certain and determined from a young age about his place in Germany, and in the world, as an artist. He was constantly challenging himself to create new styles and try new techniques, however it seems as though in his later years he took this curiosity so far and lost his signature style. There are several paintings in the galleries that I would have never believed were done by Otto Dix if they had not been included in this exhibition. For example, Vanitas (Youth and Old Age) (1932) is eerily similar to a John Currin rendition of a buxom youth; the blonde has a goddess-like, beautiful body, yet her smile if forced and absurd. In Randegg with the Vögeli (1936) Dix takes a shot at landscape painting. The pastoral, autumn landscape looks as though it could have come from the Hudson River School, rather than Weimar, Germany. The most absurd painting was attempted when Dix decided to explore biblical themes in Saint Christophorus IV (1939). Although he was clearly inspired by DaVinci’s work – as is evident in Dix’s inclusion of jagged, smoky mountains in the background – I can only assume that the artist returned to contemporary subjects shortly after this painting.

Although Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden will probably remain the first portrait I think of when speaking of Otto Dix, I will certainly think of the “War” etchings and drawings as the most important works in Dix’s career, as they were the base upon which the rest of his work was created.

Otto Dix at the Neue Galerie on view through August 30, 2010

All images courtesy the Neue Galerie Museum, New York.

RSS

RSS

I had a chance to catch Otto Dix at the Neue Galerie. I must say, I was shocked at detailed his works are. I’d suggest that everyone in the area should check it out. Very inspiring! After the show, I spent a few hours after with a hot cup of coffee in hand lost layed up in my manhattan rental apartment thinking of some of his work.

August 23, 2010 @ 3:41 pm